| Magie in het Europa van de achttiende eeuw: realiteit en perceptie. (Nele Vranckx) |

| home | lijst scripties | inhoud | vorige | volgende |

Bijlagen

Bijlage 1: BARBER, Vampires, burial, and death, 21-23.

“We saw a rather different and quite tragic scene on the same island occasioned by one of those corpses that are believed to return after their burial. The one of whom I shall give an account was a peasant of Mykonos, naturally sullen and quarrelsome – a circumstance to be noted concerning such matters. He had been killed in the fields, no one knew by whom nor how. Two days after he had been buried in a chapel in the town, it was bruited about that he had been seen walking during the night, taking long strides; that he came into houses and turned over furniture, extinguished lamps, embraced people from behind, and played a thousand little rogish tricks. At first people only laughed, but the matter became serious when the most respectable people began to complain. Even the popes acknowleged the fact, and doubtless they had their reasons. People did not fail to have masses said, but the peasant continued his little escapades without mending his ways. After a number of meetings of the town leaders and of the priests and monks, they concluded that it would be necessary – in accord with I don’t know what ancient ceremony – to wait till nine days after the burial.

On the thenth day they said a mass in the chapel where the body lay, in order to drive out the demon that they believed to be concealed in it. The body was disinterred after the mass, and they set about the task of tearing out its hart. The butcher of the town, quite old and very maladroit, began by opening the belly rather than the chest. He rummaged about for a long time in the entrails, without finding what he sought, and finally someone informed him that it was necessary to cut into the diagram. The hart was torn out to the admiration of all bystanders. But the body stank so terribly that incense had to be burned, but the smoke, mixed with exhaltations of this carrion, did nothing but increase the stench, and it began to inflame the minds of these poor people. Their imagination, struck by the spectacle, filled with visions. They took it into their heads to say that a thick smoke was coming from the body, and we did not dare say that it was incense. People kept calling out nothing but “Vrykolas!” in the chapel and in the square before it, this being the name they give to these supposed revenants. […] Several of the bystanders claimed that the blood of the of this unfortunate man was quite red, and the butcher swore that the body was still warm, from which they concluded that the deceased had the severe defect of not being quite dead, or, to state it better, to let himself be reanimated by the devil, for hat is exactly the idea they have of a vrykolakas. They caused this name to resound in an astonishing manner. And then there arrived a crowd of people who professed loudly that they had plainly seen that the corpse had not become stiff, when they carried it from the fields to the church to bury it, and that as a result it was a true vrykolakas. That was the refrain.

I do no doubt that they would have maintained that the body did not stink, if we had not been present, so stunned were these poor people from the business, and so persuaded of the return of the dead. As for us, who had placed ourselves near the cadaver to make our observations as precisely as possible, we almost perished from the great stench that emerged from it. When they asked us what we thought of the deceased, we answered that we thought him adequately dead. But because we wanted to cure – or at least not to irritate their stricken imaginations – we represented to them that it was not surprising if the butcher had perceived some warmth in rummaging, which were putrefying; that it was not extrordinary if fumes were emitted, just as such emerge from a dung heap when one stirs it up; and as for the pretended red blood, it was still evident on the hands of the butcher that this was nothing but a stinking mess.

After all of our reasoning, they were of a mind to go to the seashore and burn the hart of the deceased, who in spite of this execution became less docile and made more noise than ever. They accused him of beating people at night, of breaking in doors, and even roofs; of breaking windows, tearing up clothes, and emptying pitchers and bottles. He was a very thirsty dead man: I believe he did not spare any house but that of the consul, whith whom we lodged. However, I have never viewed anything so pitiable as the state of this island. [...]

Those citizens who were most zealous for the public good believed that the most essential part of the ceremony had been deficient. The mass should not have been said, according to them, until after the heart of this unfortunate man had been torn out. They maintained that, with this precaution, the devil could not have failed to have been surprised, and that without a doubt he would not have returned. Whereas in starting with the mass, they said, he had had all the time necessary to flee and to come back afterwards at his convience.

After all these reasonings, they found themselves in the same difficulty as the first day. They meet night and day, debate, and organize processions for three days and three nights. They oblige the popes to fast, and one sees them running among the houses, the aspergillum in their hand, sprinkling holy water and washing doors with it. With it they even filled the mouth of this poor vrykolakas. [...]

One day, as they recited certain prayers, after having planted I don’t know how many naked swords in the grave of the corpse – which they disinterred three or four times a day, acoording to the caprice of whoever came by – an Albanian, who happend to find himself in Mykonos, took it upon himself to say, in a professional tone, that it was extremely ridiculous to use the swords of Christians in such a case as this. Can you not see, you poor blind people, he said, that the guard of these swords, forming a cross with the handle, prevents the devil from leaving this corpse! Instead, why don’t you rather use Turkish sabres? The opinion of this clever man was of no use: the vrykolakas did not appear to be any more tractable, and everyone was in strange dismay. They didn’t know which saint to call upon, but with one voice, as though they had given one another the word, they began to cry out, throughout the village, that they had waited too long – it was necessary to burn up the vrykolakas entirely. After that they defied the devil to return to set up quarters there. It was better to resort to such an extreme than to have the island deserted. And in fact there was already whole families who were packing up, with the intention of retiring to Syra or Tinos. So then they carried the vrykolakas, by the order of the administrators, to the tip of Saint George’s Island, where a great funeral pyre had been prepared, with tar, out of fear that the wood, as dry as it was, would not burn fast enough for them on its own. The remains of this unfortunate cadaver were thrown on and consumed in a short time (this was the first of January, 1701). We saw the fire as we returned from Delos. You could call it a true fire of rejoicing, for no one no longer heard the complaints against the vrykolakas. They were content to observe that the devil had certainly be caught this time, and they composed a few songs to ridicule them.”

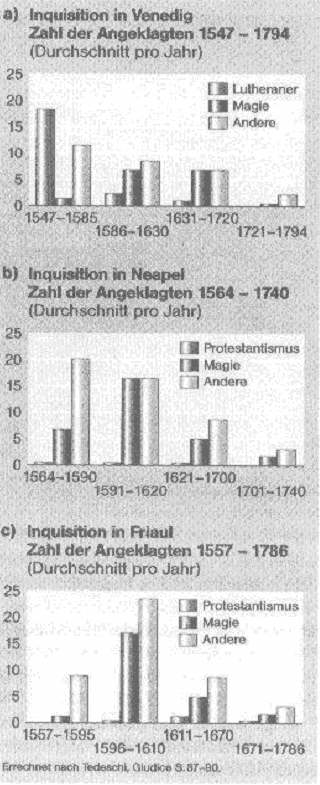

Bijlage 2: Inquisitie te Venetië, Napels en Friuli

(bron: DECKER, Die Päpste und die Hexen, 147)

Bijlage 3: Witchcraft Act, 1736

Be it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the same, That the Statute made in the First Year of the Reign of King James the First, intituled, An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft, and dealing with evil and wicked Spirits, shall, from the Twenty-fourth Day of June next, be repealed and utterly void, and of none effect (except so much thereof as repeals the Statute made in the Fifth Year of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth) intituled, An Act against Conjurations, Inchantments, and Witchcrafts.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said Twenty-fourth Day of June, the Act passed in the Parliament of Scotland, in the Ninth Parliament of Queen Mary, intituled, Anentis Witchcrafts, shall be, and is hereby repealed.

And be it further enacted, That from and after the said Twenty-fourth Day of June, no Prosecution, Suit, or Proceeding, shall be commenced or carried on against any Person or Persons for Witchcraft, Sorcery, Inchantment, or Conjuration, or for charging another with any such Offence, in any Court whatsoever in Great Britain.

And for the more effectual preventing and punishing of any Pretences to such Arts or Powers as are before mentioned, whereby ignorant Persons are frequently deluded and defrauded; be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That if any Person shall, from and after the said Twenty-fourth Day of June, pretend to exercise or use any kind of Witchcraft, Sorcery, Inchantment, or Conjuration, or undertake to tell Fortunes, or pretend, from his or her Skill or Knowledge in any occult or crafty Science, to discover where or in what manner any Goods or Chattels, supposed to have been stolen or lost, may be found, every Person, so offending, being thereof lawfully convicted on Indictment or Information in that part of Great Britain called England, or on Indictment or Libel in that part of Great Britain called Scotland, shall, for every such Offence, suffer Imprisonment by the Space of one whole Year without Bail or Mainprize, and once in every Quarter of the said Year, in some Market Town of the proper County, upon the Market Day, there stand openly on the Pillory by the Space of One Hour, and also shall (if the Court by which such Judgement shall be given shall think fit) be obliged to give Sureties for his or her good Behaviour, in such Sum, and for such Time, as the said Court shall judge proper according to the Circumstances of the Offence, and in such case shall be further imprisoned until such Sureties be given."

(bron: http://www.karisgarden.com/cunningfolk/witact.htm)

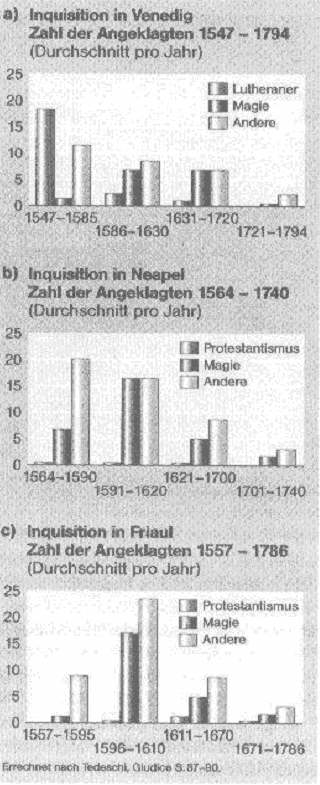

Bijlage 4: BLACKSTONE, Commentaries on the Laws of England, IV, 60-61.

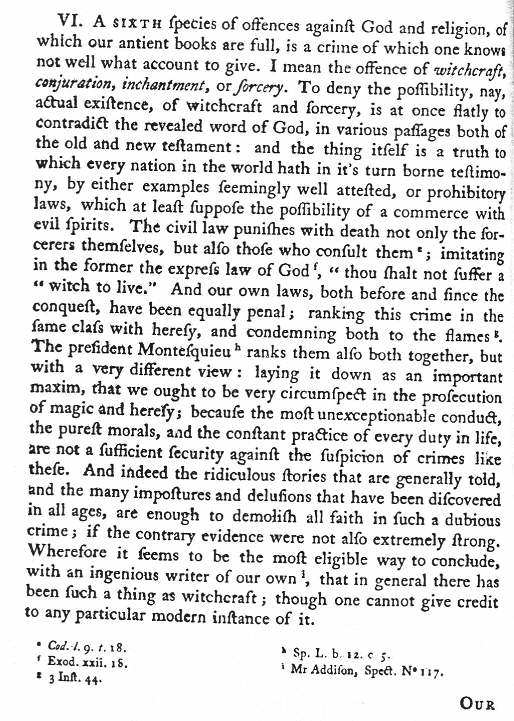

Bijlage 5: Het artikel Superstition uit de Encyclopédie

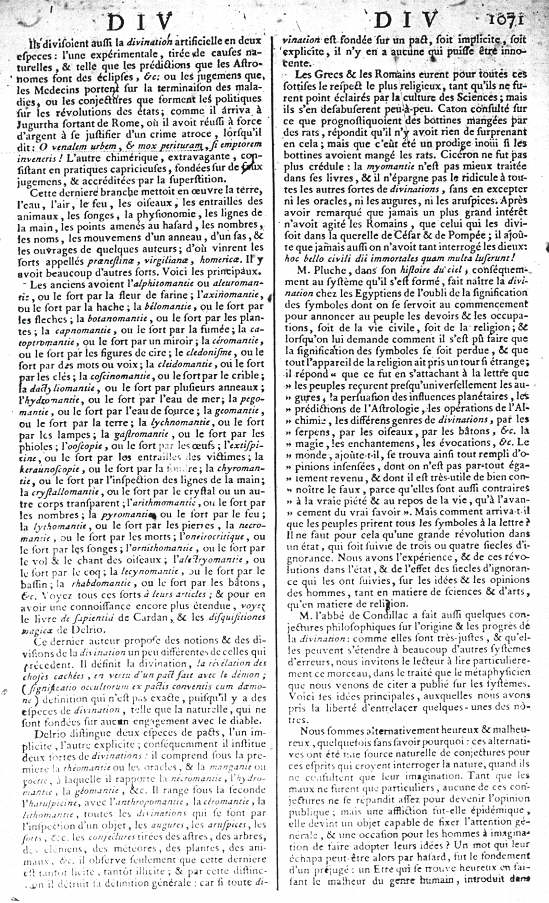

Bijlage 6: Het artikel Divination uit de Encyclopédie

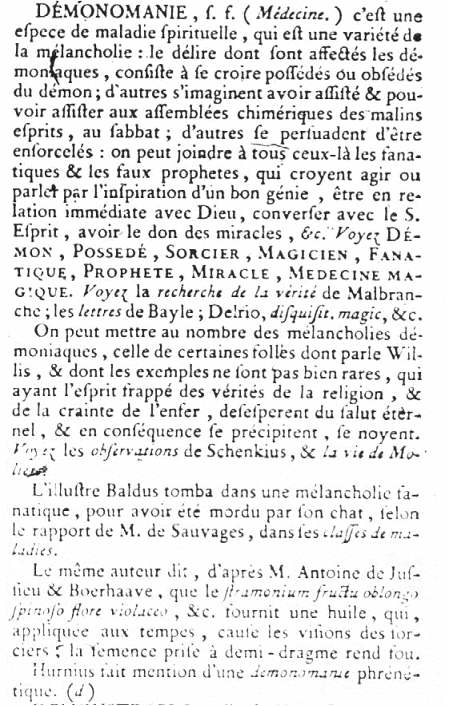

Bijlage 7: Het artikel Démonomanie uit de Encyclopédie

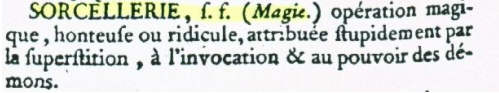

Bijlage 8: Defenitie ‘magie’ volgens het artikel Sorcellerie uit de Encyclopédie

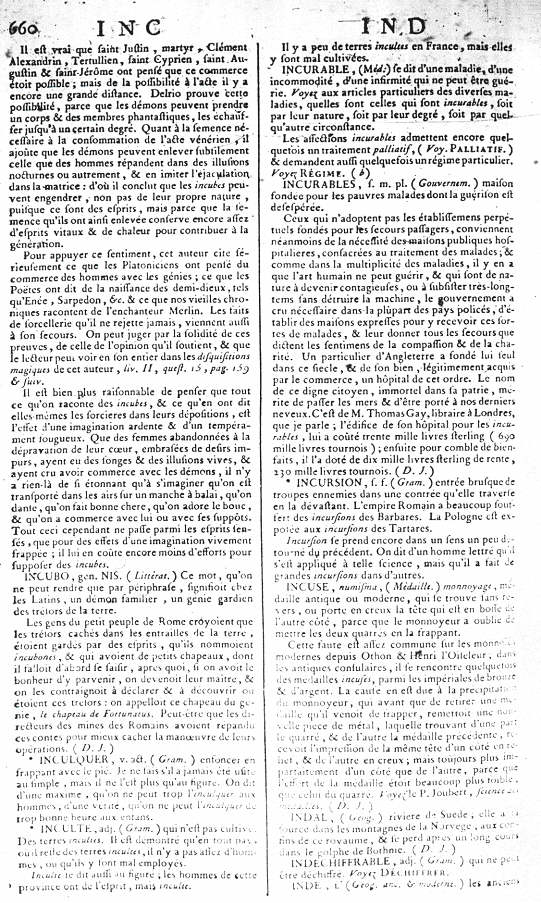

Bijlage 9: Het artikel Incube uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlagen 10 en 11: De artikels Magie en Sorciers uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 12: Het artikel Possesion du démon uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 13: Het artikel Présage uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 14: Het artikel Apparition uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 15: Het artikel Ligature uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 16: Het artikel Nécromancie uit de Encyclopédie

Bijlage 17: Het artikel Évocation uit de Encyclopédie

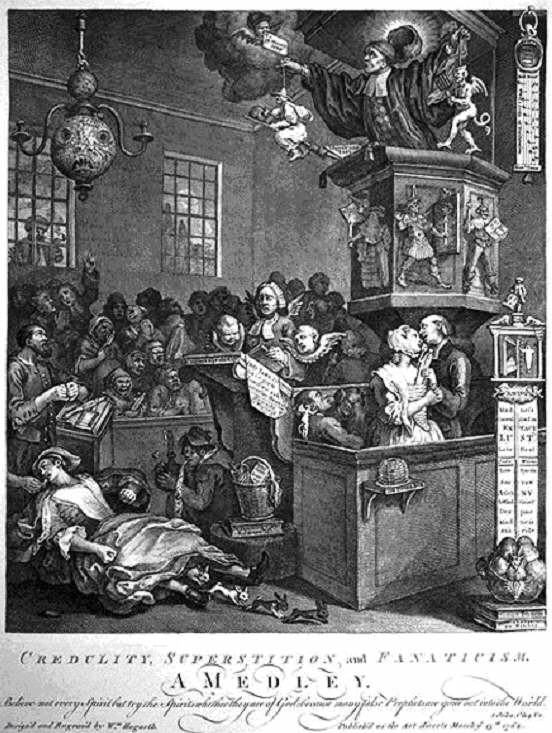

Bijlage 18: Hogarth, Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticsm (1762)

(bron: http://www.library.northwestern.edu/spec/hogarth/images/1.87.jpg)

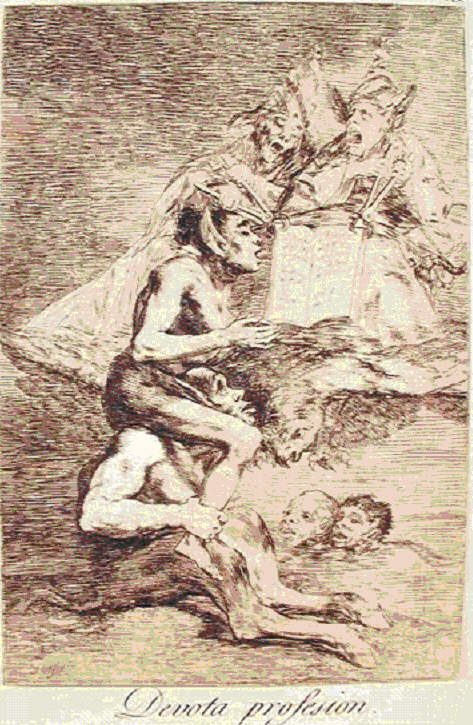

Bijlage 19: Goya, Devota Profesion (uit Los Caprichos)

(bron: http://www.bne.es/Goya/mincol/p102.gif)

Bijlage 20: Goya, Linda Maestra (uit Los Caprichos)

(bron: http://www.bne.es/Goya/maxcol/g100.gif)

| home | lijst scripties | inhoud | vorige | volgende |