| Dierenopvattingen en -voorstellingen in de stand van de kennis in de 13de eeuw. (Caroline Everaert) |

| home | lijst scripties | inhoud | vorige | volgende |

Bijlagen

Lijst met namen van autoriteiten[258]

Adelinus of Aldhelmus van Malmesbury (ca 640-709) was een Engelse dichter en werd in 705 de eerste bisschop van Sherborne. In zijn werk Liber monstrorum bespreekt hij de wonderbaarlijke volkeren. Daarnaast schreef hij verschillende Latijnse raadsels in versvorm waarin dieren, planten en stenen werden vermeld.

De Engelse augustijn Alexander Neckham (1157-1217) was geleerde in de filosofie en theologie. Hij schreef bijbelcommentaren, becommentarieerde de werken van Aristoteles en schreef De naturis rerum.

Ambrosius (ca. 1200-1280) werd beschouwd als een van de kerkvaders. Van 374 tot 397 was hij bisschop van Milaan. Zijn werk, Hexaëmeron, was gebaseerd op het gelijknamige werk van Basilius. Hierin bespreekt hij de zes scheppingsdagen.

Aristoteles (384-322 voor Christus) was een Griekse filosoof en natuurwetenschapper. Zijn logische werken, verzameld in het Organon, vormden de basis van het middeleeuwse onderwijs. Zijn natuurfilosofische werken, Liber Naturalis, werden pas in de 13de eeuw bekend in het Westen. Daaronder bevond zich het deel over de dieren, De animalibus.

De kerkvader Augustinus (354-430) was gedurende de hele Middeleeuwen een van de voornaamste autoriteiten. In 396 werd hij benoemd tot bisschop van Hippo, een ambt dat hij voor de rest van zijn leven bleef uitoefenen. Zijn voornaamste werk was De civitate dei (412-426).

Averroes of Ibn Roschd (1126-1198) was een Arabische filosoof. Hij was in de christelijke wereld vooral gekend voor zijn vertalingen en commentaren op de werken van Aristoteles.

De Arabische arts Avicenna of Ibn Sina (980-1037) raakte, net zoals Averroes, in het Westen bekend door zijn vertalingen van de werken van Aristoteles. Michaël Scotus vertaalde op zijn beurt Avicenna.

Basilius Magnus (ca. 330-379) was een Griekse kerkvader en bisschop van de provincie Caesarea. Hij schreef een werk over de zes scheppingsdagen, de Hexaëmeron.

Hieronymus (ca. 347- 419/420) was een kerkvader en filoloog. Hij maakte een vertaling van de Bijbel, de Vulgaat, die gedurende de Middeleeuwen als standaard werd beschouwd. Daarnaast schreef hij ondermeer bijbelcommentaren en heiligenlevens.

Isidorus van Sevilla (ca. 565-636) was aartsbisschop van Sevilla. Zijn encyclopedie, de Etymologiae, was een compilatie van de gehele kennis van zijn tijd. Alle gebieden van de wetenschap werden verkend. De etymologische verklaring van de woorden waren van groot belang in dit werk dat gedurende de Middeleeuwen een belangrijke bron van kennis bleef.

Jacobus van Vitry (ca. 1165-1240) was van 1216 tot 1228 bisschop van Akko (Palestina). In 1229 werd hij kardinaal van Tusculum en nog later werd hij legaat van Frankrijk en Duitsland. In zijn Historia Oriëntalis beschreef hij de geschiedenis, de geografie en de natuur van het Heilige Land.

Gaius Plinius Secundus Maior of Plinius de Oudere (23/24-79) was een Romeinse militair, magistraat en schrijver. Zijn werk Historia Naturalis met zijn talrijke natuurbeschrijvingen was een van de belangrijkste bronnen gedurende de Middeleeuwen.

Gaius Iulius Solinus (3de eeuw) baseerde zich voor zijn werk Collectanae rerum memorabilium op het hierboven genoemde werk Historia Naturalis. Hierin werden beschrijvingen verzameld die de auteur zogezegd waargenomen heeft op zijn wereldreis.

De dominicaan Thomas van Cantimpré (ca. 1201-1270) was een leerling van Albertus Magnus. Hij schreef een aantal heiligenlevens, het Liber apum (ofwel Het biënboec) en een encyclopedie Liber de natura rerum (1233-1248) dat de inspiratiebron zou zijn voor Jacob van Maerlants Der naturen bloeme.

Bijlage 1: De leeuw

1. De bronnen

a. Physiologus

“1. We begin of all by speaking of the Lion, the king of all the beasts

Jacob, blessing his son Judah, said, “Judah is a lion’s whelp” [Gen. 49:9]. Physiologus, who wrote about the nature of these words, said that the lion has three natures. His first nature is that when he walks following a scent in the mountains, and the odor of a hunter reaches him, he covers his tracks with his tail wherever he has walked so that the hunter may not follow them and find his den and capture him. Thus also, our Savior, the spiritual lion of the tribe of Judah, the root of David [cf. Rev. 5:5], having been sent down by his coeternal Father, his intelligible tracks (that is, his divine nature) from the unbelieving Jews: an angel with angels, an archangel with archangels, a throne with thrones, a power with powers, descending until he had descended into the womb of a virgin to save the human race which had perished. “And the word was made flesh and dwelt among us” [John 1:14]. And those who are on high not knowing him as he descended and ascended said this, “Who is this king of glory?” And the angels leading him down answered, “He is the lord of virtues, the king of glory” [cf. Ps. 24:10].

The second nature of the lion is that, although he has fallen asleep, his eyes keep watch for him, for they remain open. In the Song of Songs the betrothed bears witness, saying, “I sleep, but my heart is awake” [S. of S. 5:2]. And indeed, my Lord physically slept on the cross, but his divine nature always keeps watch in the right hand of the Father [cf. Matt. 26:64]. “He who guards Israel will neither slumber nor sleep” [Ps. 121:4].

The third nature of the lion is that, when the lioness has given birth to her whelp, she brings it forth dead. And she guards it for three days until its sire arrives on the third day and, breathing into its face on the third day, he awakens it. Thus did the almighty Father of all awaken from the dead on the third day the firstborn of every creature [cf. Col. 1:15]. Jacob, therefore, spoke well, “Judah is a lion’s whelp; who has awakened him?” [Gen. 49:9] [259].”

b. Aberdeens bestiarium

|

“De tribus principalibus naturis leonis.\ Phisici dicunt leonem\ tres principales naturas habere. Prima natura eius est, quod per\ cacumina montium amat ire. Et si contigerit ut queratur\ a venatoribus, venit ad eum odor venatorum, et cum cau\da sua tetigit posttergum vestigia sua. Tunc venato\res investigare eum nequeunt. Sic et salvator noster, scilicet\ spiritualis leo, de tribu Iuda, radix Iesse, filius David, cooperuit\ vestigia sue caritatis in celis, donec missus a patre descenderet\ in uterum virginis Marie, et salvaret genus humanum quod perierat.\

Et hoc ignorans diabolus scilicet humani generis inimicus, quasi pu\rum hominem ausus est temptare. Etiam hoc ignorantes qui sur\sum erant angeli, eo ascendente ad patrem, dicebant ad eos qui\ cum eo ascendebant: Quis est iste rex glorie?

Secunda natura eius est quod\ cum dormit, oculos apertos habere videtur. Sic et dominus noster cor\poraliter obdormiens in cruce, sepultus est, et deitas eius vigilibat, \ sic dicitur in canticis canticorum: Ego dormio, et cor meum vi\gilat. Et in psalmo: Ecce non dormitabit neque dormiet, qui\ custodit Israel.

Tertia natura eius est, cum leena parit catulos\ suos generat, eos mortuos, et custodit eos tribus diebus donec\ veniens pater eorum tertia die insufflat in faciem eorum et\ vivificat eos. Sic omnipotens pater dominum nostrum Iesum Christum, tertia die\ suscitavit a mortuis, dicente Iacob: Dormitabit tanquam\ leo, et sicut catulus leonis suscitabitur.

… Adversi coheunt. Nec hii tan\tum, sed et linces, et cameli, et elephanti, et rinocerontes,\ et tygrides, et leene. Fetu primo catulos quinque educant. De\ inde per singulos numerum decoquunt annis in sequentibus.\ Et postremo cum ad unum pervenerint, materna fecunditas\ reciditur, sterilescunt in eternum.

… Leontophones vocari accipimus modicas bestias.\ Que capte exuruntur ut earum cineres [A: cineris] aspergine carnes pol\lute iacteque carnes pita [A:per compita] concurrentium semitarum leones ne\cent, si quantulumcumque ex illis sumpserint. Propterea leones\ naturali eas primunt odio atque ubi facultas data est morsu\ quidem abstinent, sed dilaniatas exanimant pedum nisibus.\ |

Of

the three main characteristics of the lion.

Not knowing of his divine nature, the Devil, the enemy of mankind, dared to tempt him like an ordinary man. Even the angels on high did not know of his divinity and said to those who were with him when he ascended to his father: 'Who is this king of glory?'

The second characteristic of the lion is that when it sleeps, it seems to have its eyes open. Thus our Lord, falling asleep in death, physically, on the cross, was buried, yet his divine nature remained awake; as it says in the Song of Songs: 'I sleep but my heart waketh' (5:2); and in the psalm: 'Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep' (121: 4).

The third characteristic of the lion is that when a lioness gives birth to her cubs, she produces them dead and watches over them for three days, until their father comes on the third day and breathes into their faces and restores them to life. Thus the Almighty Father awakened our Lord Jesus Christ from the dead on the third day; as Jacob says: 'He will fall asleep as a lion, and as a lion's whelp he will be revived' (see Genesis, 49:9). ... Lions mate face to face; and not only lions, but lynxes, and camels, and elephants, and rhinoceroses, and tigers. [Lionesses, when] they first give birth, bear five cubs. In the years which follow, they reduce the number by one at a time. Afterwards, when they are down to one cub, the fertility of the mother is diminished; they become sterile for ever. ... We learn of small beasts called leontophones, lion-killers. When captured, they are burnt; meat contaminated by a sprinkling of their ashes and thrown down at crossroads kills lions, even if they eat only a small an amount. For this reason, lions pursue leontophones with an instinctive hatred and, when they have the opportunity, they refrain from biting them but kill them by rending them to pieces under their paws.[260]” |

c. Bartholomaeus Anglicus[261]

“Dat lix. ca. vander leeuwen

Leo grece dit is leeuwe in griex is

coninc in duytsch daer om dat hi coninck

ende prins is van allen beesten als ysidorus seyt

li. xij. Sommige vanden leeuwen sijn cort

ende mit cruusden manen ende dese –

en vechten niet ende sommighe sijn lang

ende mit slechten hanghenden manen

ende dese sijn fel haer voerhoeft ende

hoer start bewijst hoer moeden ende hoer

craft leyt inder borsten ende die vastich

eyt int hoeft. Ende als si gevanghen

sijn vanden iaghers so sien si in die aer

de op dat si te myn veruaert sullen we-

sen vanden iaghers die al om hem staen

ende si ontsien die crijschinghe vanden

raden des wagens mer si ontsien tuuer

meest ende si slapen mit openen oghen ende

als si wanderen so decken si hoer voet-

stappen datse die iager niet vinden en kan

ende als si geworpen hebben so slaept dat

welpen drie daghen ende dan lesten o

uermits briesschinge vanden vader wortet

gewect al beuende ende dit is een natuer

lic exempel biden mensch. want ist dat si

niet gequetst en werden so en connen si niet

toernich wesen ende in hen is oec grote ont

fermharticheyt want si en misdoen nye

mant die gaen leggen die geuanghen lu-

den die hen te moete comen laten si thuys

trecken ende si en eten gheen menschen ten waer dat si alte groten honger hadden

Hier toe heuet ysidorus geseyt li. xij. Item

plinius seyt li. viij. ca. xvij. Dat die leeu

wen in sijnre hoechke edelheyt is wan

neer dat hem sijn hals ende sijn scouderen

ouer al mitten manen bedect sijn ende die

leeuwen die de pardy winnen en heb-

ben die edelheyt niet Item die leeuwe be-

kent wel als die lewin mitten pardus ge

hilict heeft ende dan so bijt hijse ende slaet-

se mer mocht si erghent aen een water

comen dat si hoer wasschen mocht so en

wister die leeuwe niet af ende als si der ion

gen geneest so wert hoer die buke van-

den claeuwen der iongen geschoert en-

de dair om en baert si niet dicwijl plinius

seyt dat si eerst vijf ionghen brengt daer

na vier ende also alle iaer een pyn ende si

sijn int eerst ongeforineert ende cleyn ter

grootheyt van enen wesel int begin ende

hi seyt oec dat si ter sester maent nauwe

geboren mogen werden ende tot twe en maen

ten nauwe beroert en werden Item die

leeuwe pist als een hont die tbeen op

licht ende die orine stinct seer vuyl | ende als

hi eens sat is so mach hi drie dagen vas-

ten ende ist dat hi te veel ghegeten heeft

so werpt hi die spise in een fonteyn. Ende

als hem honghert so haelt hise mitten

claeuwen weder wt ende hi en werpt die spi

se niet wt dan als hi geiacht wert op

dat hi te bat vlyen mach of lopen Item

hi mach alte langhe leuen twelc bekent

wort bijder verteringe van sinen tanden

ende dan is sijnre ontheyt als hi qualiken

arbeyden mach so et hi wel menschen

ende dan pleghen si omtrent den steden te

wesen ende wachten tvolc dat te velde co

met ende alsmense vangt so werden si ge

hangen op dat si te meer veruaert sullen

wesen si gripen die mannen wel. Mer op

ten wiuen grimmen si slecht est en doen

hem niet dien ionghen kinderen misdoen si

selden ten waer dat si alte grote honger

hadden ende wanneer dit die leeuwen toer-

nich sijn so slaet hi die aerde eerst mit si

nen staert ende dair na verheft hen sijn moet

so smijt hi sinen rugge hardeliken mit

sinen start weder ende wt alle wonden die

hi maect mitten nagelen of mitten tan-

den dair loept scarpe ende wreet bloet wt

als ysidorus seyt Item als hi in groter vre-

sen is van sinen liue als hem die honden

also na comen dat hi qualiken ontgang-

een mach so openbaert hi sijn edelheit

want hi en wil niet sculen in heyughen

noch in hagen mer hi gaet sitten op een

schoen velt ende hi saet hen daer toe dit hi

hem weren wil also langhe als hi staen

kan ende comt toe springhen mit groten

spronghen ende schoert die honden ende als

hi gewont wort dat weet hi also nauwe

wie hem dat ghedaen heeft ende in sinen

aenganck pijnt hi hem vlichs den recht

sculdigen te gripen hoe veel datter sijn

ende als yemant na hem schiet ende hijs niet

en raect so werpt hi dien neder mer hy

en quetsten niet ende screyt of stort tranen wt si-

nen oghen ende als hi siecke is so mey

stert hi hem seluen mit apenbloet Itez[262]

hi ontsiet seer eens hanen kam ende sinen

sanck ende hi is een bequaem dier beken

nende ende minnende die hen goet doet alst

openbaert inden exempelen die plinius

daer seyt Hier toe henet plinius gheseyt

li. xij. ca. xvij. Vanden leeuwe seyt aristo

tiles li. ij. Ende alsoe doet avicenna dat die

leeuwe heeft enen hals of hi onberoer

lic waer ende stijf ende sijn binnenste sijn of si

van enen honde waren ende altoes roert

hi den rechteren voet eerst ende na den laf

teren als die kemel doet ende hi heeft lut

tel morchs inden benen ende sijn benen sijn

hart want waert datmen daer harde op

sloeghe het sonde schinen of daer vier

wt spronghe Item li xvi. seyt hi dit die

leeuwe veel spieren in sinen voeten heeft

ende daer om wint hi blinde kinder als dye

hont of die wolf ende hi heeft gesaechde

tanden ende daer om wint hi zonen dye on

volcomen sijn als die selue seyt ende so

linus mede die welke seyt soe wanneer

datmen enen ionghen hont slaet ende hy

ianct so is die leeuwe veruaert wes kinder

blint werden gheboren Item hi bercht

hem in hogen bergen ende daer siet hi si-

nen roef ende als hi den roef siet so reert

hi also lude van welker stemmen die ander

dyeren veruaert sijn ende bliuen vluchs

staen ende so coemt hi dair bi ende maect om

me die dyeren een cirkel daer die dieren

niet ouer en dorren gaen ende bliuen staen

of si doot waren recht of si verwijst wa

ren te steruen ende verdeyden sijns daer oft

haer coninc wear Item als hi ouer scar

pe steenroetsen of sireuellen gangen sal

so trect hi sijn claeuwen in ende huutse want

die claeuwen oerbaert hi voer sijn swaert

ende daer om trect hijse binnen sinen vley

sche op dat si niet gequetst en sullen wer

den ende hi scaemt hem den roef alleen te-

nen die hi geuanghen heeft ende dair om

laet hi den anderen beesten wat die hen

volgen van sijnre gracien die hi geroeft

had als die selue seyt Item hi is alsoe

heet van naturen dat hi coertsen crijcht

die den quarteyn bouen gaen ende dese

suuct heeft hen die nature ghegheuen op

dit hem sijn wredicheyt benomen sal wer

den Item sijn vleysch wantet alte sonder

linge hete is so ist quaet gheten als dy

ascrodies seyt ende plinius mede li. xxviij.

ende is oec goet in medecinen tot veel din

gen was smeer den serpenten contrari

is ende so wie daer mede besmeert is die

en darf niet zorgen voer enighe steecten

van venijnden wormen Item sijn vet gemengt mit roesolien beschermt die huut

vanden aensicht van laster ende van quaden

placken ende behout die witheyt ende ghe-

neest verbarntheyt | ende sijn gal mit wa-

ter ghemengt gheneest swellinghe der

oghen ende maectse claer ende is oeck goet

teghen die vallende suucten Item sijn

hert in spisen genomen den quar

teyn. Hier toe heuet plinius gheseyt li.

xxviij. ca. viiij. Item wanneer datmen den

leeuwe iaecht so maectmen enen dub-

belden cule den enen vluchs aen den an

deren ende inden anderen cule dair wort

een starke houten kist geset die lichteli

ken toeualt als si geraect wert \ ende men

set een scaep inden eersten cule ende dair

springt hi in naden scape ende so valter

vluchs een bort bouen op dat seer swaer

is also dat hi bouen niet weder wt en mach

ende als hi dan siet dat hi verscalct is soe

vliet hi voert inden anderen kule die daer

aen staet mitter houtenre kisten die soe

beheyndeliken ghemaect is mit eenre

vallen dat die kist vast toe sluyt als dair

yet coemt ende daer blijft hi in geuangen

ende dan comen die iaghers toe ende nemen

minen lieuen here mitter kisten ende voe

renen wech ende houdenen alsoe langhe

daer rhent hi getemdt wert ende dit roert

iheronimus ouer ezeetchiel xix. ca. al-

daer hi seyt \ si seynden hen in een keuye

of in een kist

Dat lx. ca. vander leeuwinnen

Leena dat is twijf vanden leeuwen

ende is een beest die seer gheyl is al

toes soude si wel hyliken ende daer om is

si wreeder dan die leeuwe ende sonderlin

ge als si iongen heeft want si avontuert

hoer lijf om haer kinder want si en ont

siet dat scut der iaghers niet op die tijt

. Item si baert veel ionghen ter eerster

dracht ende meer dan na ende daer om wert

haer moeder inden liue gequetst vanden

nagelen der iongen ende also draecht si al

le iaer myn als aristotiles ende plinius seggen

ende dese gelikenis seyt ysidorus li. Xij. Item

die dyeren mitten scarpen naghelen en

mogen niet dicwijl baren want si verder

uen die moeder daer si in leggen als si

hem inden liue bestaen te rueren Item

daer is een cleyn beestken dat alte seer ont

sien wert vanden leeuwe ende vander leeu-

winnen twelc opraleo hiet want het dra

get eenre hande venijn dat den leeuwe

ende den leeuwinne doot ende wanneer dat

beestken geuangen wert so barment ende

bestroyter vleysch mede mitter asschen

ende dat vleysch leytmen inden weghen

daer die leeuwen pleghen te wanderen

ende als si dat vleysch eten so steruen si als

ysidorus seyt li. xij. Item als auicenna

seyt li. vij. ca. i. so is die leeuwen een vra

tich dier inder spisen want hi et ende slijnt

sijn spise sonder kauwen ende daer om spu-

wet hi dicwijl wt dat hi ghegeten heeft

ende dat hi wt gheworpen heeft dat et hi

weder also dat hi swaer wert vander spi-

sen ende daer na vast hi twe daghen ende

twe nachten ende hi en doet sijn gevoech

niet dan tot tween daghen eens ende dat

is droghe sonder nat ende stinct seer vuyl

ende also doet sijn orine oec ende wanner dit

sijn buke op gesneden wert so coemter

een quade lucht wt ende hi heeft enen stinc

kenden adem die venijnt is ende sijn be-

ten sijn venijnt sonderlinge als hi raest

hi wort rasende als die hont doet als a

ristotiles ende auicenna segghen ende hi is

seer fel als hi toernich is ende hi pleecht

hem seluen mitten staert op sinen rug-

ge te slaen ende grimt leliken mit sinen tan

den sonderlinghe als hi honger heeft

ende hi pleecht in gaten ende in holen te scu-

len ende gripen die dyeren die verbi hem

liden ende springt hem op tlijf ende scoertse

ende breect hem vleysch been ende huut ende

etse ende siet hi yemant comen die hem

den roef nemen wil so grijpt hi sinen roef

vast mit sinen claeuwen in sinen armen

ende grimt ende siet ansteliken den ande

ren aen ende smijt die aerde starkelijck

mit sinen start ende ist dat yemant bi hem

coemt dien vaert hi opt lijf ende scoertse

ende dan loept hi weder tot sinen roef

Item als hi eerst enich dier gevanghen

Heeft so drinct hi dit bloet eerst van dien

Dier ende lecket ende na deylt hi die le

Den ende breectse van een ende slijndet

vleysch”

d. Albertus Magnus

“58. LEO (Lion) is represented by three species; one is short, with much hair on its neck and is relatively weak; another is slender, as if spawned by a leopard, and is timid in character; the third is long and displays enormous strength. |107| The lion is a lordly animal which delights in mighty and generous deeds, whence it is called “king of the beasts.” because it is disposed to share its prey with other animals, it disdains to provide for the morrow; after eating its fill, it is reluctant to return to leftovers of its feast but allows them to be taken by any animal, especially by man whom it seldom attacks and kills unless prompted by great hunger when no other food is available. With its formidable strength the lion claws and dismembers those that oppose and challenge its superiority; and beg for mercy. While a lion rarely shows fear, it has a unique hatred for the scorpion and invariably takes flight when it encounters one. According to some reports it is also afraid of a white rooster.

When a lion is tamed, the training is enforced at the crack of a whip. If a lion is satiated by overeating, it sticks a paw down its throat to induce vomiting, especially when it anticipates running at full tilt in flight; scarcely ever will it eat a second meal before the first one is digested. (...)

Some contend the lion suffers continually from quartan fever, but this is patently absurd since nature produces no animal which lacks a balanced humoral constitution suited to its specific needs and designed to preserve its health under ordinary conditions. Sometimes when a lion takes sick, it preys on an ape and, after eating the ape’s flesh, is cured of its ailment. Occasionally it drinks a dog’s blood for the same purpose. The greasy fat of the lion has hotter quality than the fats of all other animals; for this reason every animal, even snakes, shies away from anyone who is smeared with lion grease. The vertebrae in a lion’s neck are intimately connected and the adjacent flesh is tough and rigid, giving the entire neck a tendinous character which prevents the lion from turning its head and looking backward. Its interior parts are like those of a dog, not expecting the fanglike teeth, though the lion’s are larger; however its external appearance more resembles a cat. When a lion traverses stony ground, it retracts its claws to protect them from damage, treating them as weapons to be spared for conflict.[263]”

e. Brunetto Latini

“CLXXIIII DEL LION

LION est apelés selonc la langue as grizois, ki tant vaut dire comme rois en nostre parleure. Car lion est apelés rois des bestes, pour ce que la ou il crie toutes bestes s’enfuient comme se la mors les cachast; et la u il fait cercle de sa coue, nule beste n’ose passer par enki. 2. Et nanporquant lyon sont de. iii.manieres; car li .i. sont brief et ont les crins crespes et sont sans bataille, li autre sont lons et grans et ont crins simples et sont mervilleuse fierté. Et lor corage sont demoustré par le front et par sa coue, et sa force est en son pis, et sa fermeté est en son chief. 3. Et ja soit ce k’il est redoutés de tous animaus, neporquant il crient le blanc cok et la tumulte de roës, et feus li fet grant paour. Et d’autra part li escorpions li fet mal trop grant se il le fiert, nés le venin dou serpent l’ocist. 4. Car cil ki ne soufri pas que nule chose fust sans contraira volt bien ke li lions ki est orgilleus et fors sor toutes choses, et ke par sa grant fierté ensit proie tozjours, eust des choses ki l’enpechent contre sa cruauté, dont il n’a pooir k’il s’en deffende; et entre * ce est il si malades autresi con de fievre les .iii. jours de la sesmaine, ki mout amenuise son orguel. Et nanporquant nature li ensenge a mangier le siguë, ki le garist de sa maladie. (…)

7. Et sachiés ke lyon gisent envers, li malle avec femele, autresi come les cers et comme cameus et olifans et unicorn et tygres, et si engendrent .v. fiz a la premiere porture; mais la force k’il ont es ongles et es dens et en tout le cors empire molt la matrice sa mere, tant come il sont dedens. Et a lor naistre issent en tel maniere que la seconde fois li leus ou la mere reçoit la semence son malle n’a pooir que il engendrent que .iiii., et a la tierce fois trois, et a la quatre fois .ii., et a la quinte .i. De lors en avant est cil leus si gastes k’il ne conçoit jamés tote en lor naissance, li lionceaus sont si esbahi k’il en gisent en pasmison .iii. jors, autresi come s’il fussent sans vie; tant que lor peres vient au chief de .iii. jors, ki les escrie si fort de sa vois que li fiz s’esdrecent et ensivent lor nature. 9. L’autre maniere de lyon sont engendré d’une beste ki a non parde, et teus lyons sont sans crins et sans noblece et sont conté entre les autres vils bestes. (…)[264]”

f. Jacob van Maerlant[265]

“Leo segt solinus jeeste

es coninc van iiij. voeten beeste

leo es hi oec ghenant

ende liebard es hi in dietsch becant

men vindet oric visiren

van liebarden iij. manieren

curte vintmen als ende als

ru gheard kersp inden als

mar die ne sijn no starc no snel

andre vintmen also wel

dat perdus winnete dat wreede dier

die ne sijn no wreet no fier

noch oec inden als oec gemaent

mar edele lione als men waent

sijn lanc ende smal ende slecht yard //

snel ende starc ende onueruard

sine weten ghene scalchede

no negheen bedrieghen mede

simpel es die sien van desen

ende also wilsi besien wesen

hare uoroft ende start doet

verstaen hoe hi es ghemoet

jn barste ende in uoete uoren

ligghen are crachte als wijt oren

so et si si alsi riden

hare ghenoete willen tallen tiden

die liewinne brinct eerst .v. jonghe

dan iiij. ten andren spronghe

dan iii. Dan .ii. dan .j.

dar na nemmermee negheen

twe spenen euet ende die clene

middel an haren buuc allene

augustinus die seget

alse die lewinne hare jonc leget

dat sj in .iij. draghen ne waken

dan comt die vader claghe maken

ende grongieren ende mesbaren

dan onwaecsoe te waren

ende dese slaep ghelijct der doet

dits van beesten wonder groet

solinus seit in sijn gedichte

men quetsene hine belcht niet lichte

mar maecmenne erre so es uerloren

al dat hem qomt te uoren

nochtan sparti dats heren doen

twi draghen si in den scilt .i. lioen

ende sine int herte niet draghen

vindsi were si laten em jaghen

mar den armen ende den verwonnen

dies dien sparen niet connen

vint dat lion oec sonder waen

enen man die was gheuaen

dien ne comti altoes niet an

no uerbitet oec den man

het ne dadem ongher alte groet

onder oec hi den man doet

dan twijf dats grote edelhede

ende ouder doeti urouwen mede

dan magheden onbesmet

alsi slaept sine oghe let

ne wert yloken nemmermee

gati in sande of in snee

hi dect met sinen starte dan

sijn spor om dattene die man

nie ne vinde also ghereet”

2. Illustraties

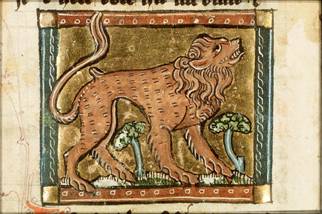

JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, KA 16, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1350. [http://racer.kb.nl/pregvn/MIMI/MIMI_KA16/MIMI_KA16_059V_MIN_B1.JPG], folio 59vb°.

JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, 76 E 4, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1450. [http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/thumbsa300/76E4_022R_MIN_B1M.JPG], folio 22rb1°.

Bijlage 2: De eenhoorn

1. De bronnen

a. Physiologus

“XXXVI. On the Unicorn

In Deuteronomy Moses said while blessing Joseph, “His beauty is that of the firstling bull, and his horns are the horns of the unicorn” [Deut. 33:17]. The monoceras, that is, the unicorn, has this nature: he is a small animal like the kid, is exceedingly shrewd, and has one horn in the middle of his head. The hunter cannot approach him because he is extremely strong. How then do they hunt the beast? Hunters place a chaste virgin before him. He bounds forth into her lap and she warms and nourishes the animal and takes him into the palace of kings.

The unicorn has one horn because the Savior said, “I and the Father are one” [John 10:30]. “For he has raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David” [Lk. 1:69]. Coming down from heaven, he came into the womb of the Virgin Mary. “He was loved like the son of the unicorns” [cf. Ps. 22:21] as David said in the psalm.

[He is said to be shrewd since neither principalities, powers, thrones, nor dominations can comprehend him, nor can hell hold him. He is small because of the humility of his incarnation. He said, “Learn from me; for I am gentle and lowly in heart” [Matt. 11:29]. He is so shrewd that that most clever devil cannot comprehend him or find him out, but through the will of the Father alone he came down into the womb of the Virgin Mary for our salvation. “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” [Jon 1:14]. The unicorn is like the kid, as is our Savior according to the Apostle: “He was made in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin he condemned sin in the flesh” [cf. Rom. 8:3]. This was spoken well of the unicorn.][266]”

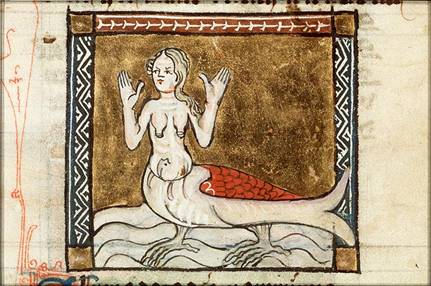

b. Aberdeens bestiarium

|

“De monocero\ Est monoceros monstrum\ mugitu horrido, equino\ corpore elephantis pedibus, cau\da simillima cervo. Cornu\ media fronte eius protenditur\ splendore mirifico, ad mag\nitudinem pedum quatuor, ita\ acutum ut quicquid impe\trat [A: impetat] facile ictu eius foretur.\ Vivus non venit in homi\num potestatem, et interimi quidem potest, capi non potest.\” |

“Of the monocerus

|

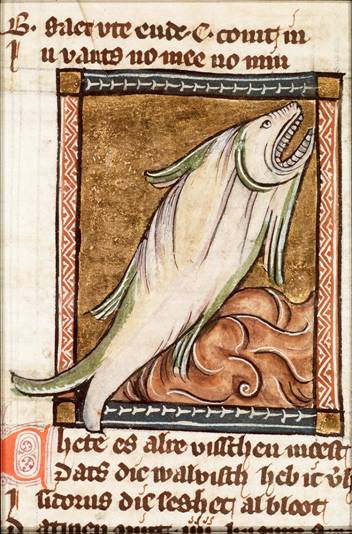

c. Bartholomaeus Anglicus[268]

“Dat lxxxiiij. ca. vanden eenhoern

Rinoceron in griex dat is cornulo

nare in latijn ende eenhoern in duyt

sche dat selue is oeck monoceron ende is

alte wreden beest ende heeft enen hoern

voer in thoeft staen van vier voeten lang

ende is ouer starck ende scarp ende soe wat hi

daer mede raect dat gaet doer als ysi-

dorus seyt li. xij. want hi heeft dicwile

vechtinghe mitten elephant ende dien

quetst hi can hi daer toe comen ende hi

weet wel dat hi nergent crancste en is

dan inden buke ende daer om steect hi al-

toes naden buke des elephanten ende de

sen eenhoern en machmen qualiken van

ghen dan in deser manieren als die au

toers scriuen vanden naturen der dinghen

Men set hem een meysken voer dat een

reyn maecht is ende dan coemt die een-

hoern ende begeeft alle sijn wreetheyt ende

leyt sijn hoeft inder maechden scoet ende

wert onstlaep ende dan wert hi geuangen

ende wert doot geslagen mitten scotten der

iageren. hier toe heuet ysidorus geseyt li.

xij. Item gregorius seyt ouer iob Dat de-

se eenhoern alsoe fel is ende also onghe-

temt van naturen waert dat hi mit e-

niger subtilicheyt geuangen worde men

mochts niet leuende houden dat hi them

men soude willen mer hi sterft vluchs

Item plinius seyt van desen li. viij. ca.

xxi. p dat hi midzen op tvoerhoeft in-

den nazegaten te midswegen vander na-

sen enen hoern heeft ende is viant des e

lephants ende hi wettet ende scueret sinen

hoern theynden opten roetsen op dat hi

te bat rede sal wesen te vechten Item die

selve seyt li. xxij. ca. xxij. datter veel spe

cien sijn van desen dier / als rinoceron

monoceron ende egliceron ende monoceron

is een wrede wilde beest die den heynst

gelijc is inden lichaem ende den herte in

den hoefde ende den elephant inden voe

ten ende den beere inden start ende geeft een

sware stemme wt ende heeft enen swarten

hoern wt blickende midzen in tvoerhoeft

van tween cubitus lanck dese beest en

machmen leuende niet vanghen ende egli

ceron is een speci vanden eenhoern en-

de hiet in latijn capricornus van egle in

griex dat is capra in latijn ende gheyt in

duytsch ende van ceros in griex dat is

hoern in duytsch ende is een cleyn dier

dat den hueken gelijc is ende is alte wreet

ende draecht enen hoern voer in thoeft

Item plinius seyt aldaer dat in indien sijn

ossen mit enen hoern ende hebben witte

spockelen ende vaste ende dichte claeuwen

als die paerden ende daer sijn oeck ezels

mit enen hoern als aristoteles auicenna ende

plinius segghen want dese hebben enen

hoern staen tusschen horen oren ende dat

ander lijf is als die wilde ezel ende alsul

ken eenhoern en is also fel niet noch soe

koen als die ander. Ende monoceros wert

geseyt van monos in griex dat is een in

duytsch ende ceros dat is eenhoern

dat es te samen een dier hebbende een

hoern in sijn voerhoeft ende wert ghede-

clineert Nom hic rinoceron gto huius ri-

nocerontis ende men vint oeck rinoceros

ende monoceros ende dan seytmen in geni-

tiuo rinocerotis ende also vanden anderen”

d. Albertus Magnus

“|144| 106. UNICORNIS (Single-horned rhinoceros) has a modest size in relation to its tremendous power. The color of its hide resembles boxwood, and its feet are divided into two hooves. These inhabitants of hilly and desert districts grow a sizable horn on their forehead. Using this horn which they sharpen by honing it on rocks, they are able to pierce hide of an elephant, and they have no fear of hunters. The famous Pompey once exhibited this animal at a spectacle in Rome.

It is alleged the rhinoceros is so charmed by virgin maids it become gentle and even soporific in their presence, so it can be captured and bound. A young rhinoceros can be caught and tamed[269].”

“|119| 71. MONOCEROS (Rhinoceros) has a horrifying bellow. In form it seems to be a composite of several animals, for it has the body of a horse, the feet of an elephant, a swinelike tail and a cervine neck. Growing from the center of its forehead is a stately horn of wondrous splendour, sometimes attaining a length of four feet, and so sharp it readily pierces anything into which it is thrust. Rarely can this animal be capture, much less tamed, and there are virtually no reports of its submitting in the live state to man’s governance. In fact, when it sees that it may be overcome, it kills itself in a blind rage[270].”

e. Brunetto Latini

“CLXXXXVIII JA PARLE DE L’UNICORNE

Unicorne est une fiere beste auques ressemblable a cheval, de cors; mais il a piez d’olyfant, coue de cerf, et sa voix est fierement espoenatable; et enmi sa teste a une corne, sans plus, de merveillouse resplendor, et a bien .iiii. piez de lonc, mais il est si forz et aguz que il perce legierement quantque il ataint. 2. Et sachez que unicor est si aspres et si fiers que nul ne la puet attaindre ne prendre par nul laz dou monde: bien puet estre qu’il soit occis, mais vif ne le peut on avoir. Et neporquant li veneor envoient une vierge pucele cele part ou li unicor converssent; car c’est sa nature que maintenant s’en vait a la pucele tout droit et depose toute fierté, et se dort souef en son sain et en ses dras. En ceste maniere le deçoivent li veneor[271].”

f. Jacob van Maerlant

“Vnicornus ludet .i. horen

espentijn heetement als wijt horen

rinocheros heetet in dietscher wort

(…)

ons scriuet iacob van vitri

ende sente isidorus de meester vri

hoement vaet ende niet ne iaghet

men nemet ene ombesmette maghet

ende setse alleene in gheen woud

daer hem dunicornus houd

dar comet dat dier ende siet hane

dat reine ulesch de soete ghedane

ende werpet dar wech ende af doet

allen fellen houermoet

ende anebedet die suuerede

sijn houet met groter goedertierede

ende leghet in der ioncurouwen scoet

ende slapet daer met gnoechten groot

so coment die jaghers mettien

ende vanghent al onuersien

si slaent doot na hare gheuoech

ofte si bindent vaste ghenoech

ende bringhent in palaisen dan

hoghen heren te scouwene an

dit wreede dier dit espentijn

dinket mi .i. bedieden sijn

vanden godes sone die sonder beghin

es ende was indes vader sin

ende dar onse ulesch an nam

want heri andie maget quam

was hi in emelrike wreet

ende uerstac die inglen leet

huten emele onder derde

om hare dorpere houarde

[in arderike balch hi mede

om sine ouerhorechede]

vp onsen hersten vader adame

ende hi toghedem sine grame

den quaden sodomiten mede

om hare groote onsuuerhede

ende om hare gulseit also wel

den kindren van israel

dit vnicoren dese eneghe sone

ne leuede inde werelt de gone

diene enechsijns adde belaghet

sonder maria de soete maghet

die alleene alst es an scine

sat inder werelt wostine

alleene was soe want hare ghelike

ghebreket in dat arderike

hare hoemoede hare suuerhede

daden den sone der ewelicheden

vergheeten sine wreeteit groot

ende beete neder in haren scoet

dats in haren lachame reine

dar hi sonder mans ghemeine

den menschelic roc ane dede

tonser alre salichede

jn desen roc sonder waen

hebbene de iagers gheuaen

alse inder reinre maghet scoet

dat sijn de ioden diene doot

sloeghen al sine daer vonden

die dar naer in curten stonden //

van doode te liue up was ghewect

ende inden hoghen palaise ghetrect

met sinen eweliken vader

dar die heleghen sijn algader[272]”

“Monocheros verstaet mi wale

ludet enoren in dutsche tale

plinius segt ende solijn

dat cume vreseliker dier mach sijn

sijn luud elken man veruart

ghescepen est als i pard

gheuoet na thelpen diere

gheouet na des erts maniere

na swijn ghestart als wijd oren

midden in den ouede voren

raghet hem .i. horen so clar

iiij voete lanc es hi dats war

so scarp dar mach niet jeghen staen

men macht bi ghenen angiene vaen

maer niet ghetemmen hoe soet sj

ons seghet jacop van vitri

dat gheen leuende man vaet

want eist so datment belacht

ende hoet hem siet in smans hoede

het bliuet doet van ouermoede

dit nes deenoren niet dat verstaet

dat die reine maget vaet[273]”

2. Illustraties

Monoceros in: The Aberdeen Bestiary, [http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/comment/15rmonocero.hti], Ms. 24, folio 15r°.

Monocheros (vis) in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, KA 16, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1350. [http://racer.kb.nl/pregvn/MIMI/MIMI_KA16/MIMI_KA16_107V_MIN_B1.JPG], folio 107vb1°.

Monocheros (vis) in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, 76 E 4, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1450. [http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/thumbsa300/76E4_068R_MIN_B2M.JPG ], folio 68rb2°.

Unicornus in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, KA 16, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1350. [http://racer.kb.nl/pregvn/MIMI/MIMI_KA16/MIMI_KA16_071R_MIN.JPG], folio 71r °.

Unicornus in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, 76 E 4, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1450. [http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/thumbsa300/76E4_034R_MINM.JPG], folio 34r °.

Monocheros in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, KA 16, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1350. [http://racer.kb.nl/pregvn/MIMI/MIMI_KA16/MIMI_KA16_063R_MIN_B2.JPG], folio 63rb2°.

Monocheros in: JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, 76 E 4, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1450. [http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/thumbsa300/76E4_026V_MIN_AM.JPG], folio 26va °.

Bijlage 3: De arend

1. De bronnen

a. Physiologus

“VIII. On the Eagle

David says in Psalm 102, “Your youth will be renewed like the eagle’s” [Ps. 103:5]. Physiologus says of the eagle that, when he grows old, his wings grow heavy and his eyes grow dim. What does he do then? He seeks out a fountain and then flies up into the atmosphere of the sun, and he burns away his wings and the dimness of his eyes, and descends into the fountain and bathes himself three times and is restored and made new again.

Therefore, you also, if you have the old clothing and the eyes of your heart have grown dim, seek out the spiritual fountain who is the Lord. “They have forsaken me, the fountain of living water” [Jer. 2:13]. As you fly into the height of the sun of justice [Mal. 4:2], who is Christ as the Apostle says, he himself will burn off your old clothing which is the devil’s. therefore, those two elders in Daniel heard, “You have grown old in wicked days” [Dan. 13:52]. Be baptized in the everlasting fountain, putting off the old man and his actions and putting on the new, you who have been created after the likeness of God [cf. Eph. 4:24] as the Apostle said. Therefore, David said, “Your youth will be renewed like the eagle’s” [Ps. 103:5].[274]”

b. Aberdeens bestiarium

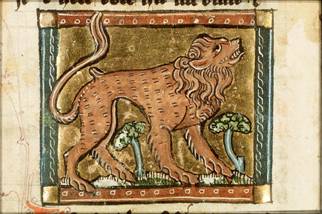

|

“De aquila / Aquila ad acumine oculorum vocata, tanti enim dicitur esse\ contuitus ut super maria immobili penna feratur nec\ humanis pateat obtutibus de tanta sublimitate pisciculos na\ tare videat ad tormenti instar descendens, raptam predam pen\ nis ad litus pertrahat.

Cum vero senuerit, gravantur ale ipsius, et\ obducuntur caligine oculi eius. Tunc querit fontem et contra eum\ evolat in altum usque ad aerem solis, et ibi incendit alas suas\ similiter et caliginem oculorum exurit in radio solis. Tunc de\ mum descendens in fontem trina vice se mergit, et statim reno\ vatur in multo vigore alarum, et splendore oculorum.

Sic et tu\ homo qui vestimentum habes vetus, et caligant oculi tui, que\ re spiritualem fontem domini et eleva mentis oculos ad deum qui est\ fons iusticie et tunc renovabitur sicut aquile iuventus tua.

Asse\ ritur quoque quod pullos suos radiis solis obiciat, et in medio ae\ ris ungue suspendat. Ac siquis repercusso solis lumine intrepidam\ oculorum aciem in offenso intuendi vigore servaverit, is probatur\ quod veritatem nature demonstravit. Qui vero lumina sua radio\ solis inflexerit, quasi degener et indignus tanto patre reicitur\ nec estimatur educatione dignus, qui fuit indignus suscep\ tione. Non ergo eum acerbitate nature, sed iudicii integritate con\ dempnat.

Nec quasi suum abdicat, sed quasi alienum recu\ sat. Hanc tamen ut quibusdam videtur regalis avis inclemen\ tiam plebeie avis excusat clementia. Avis cui nomen fulica\ est, que Grece dicitur fene, susceptum illum sive abdicatum, si\ ve non agnitum aquile pullum cum sua prole connectit, atque intermiscens suis eodem quo proprios fetus materne sedulita\ tis officio, et pari nutrimentorum subministratione pascit et\ nutrit.

Ergo fene alienos nutrit, nos vero nostros inimici crudeli\ tate proicimus. Aquila enim si proicit, non quasi suum proicit, set\ quasi degenerem non recognoscit, nos quod peius est quos no\ stros recognoscimus abdicamus.\

(…) Aliter. Sicut aquila\ volans ad escam. Aquila enim alto valde volatu suspen\ ditur, et annisu prepeti ab ethere libratur, sed per appetitum ven\ tris terram expetit, seseque a sublimibus repente deorsum fun\ dit.

Sic sic humanum genus in parente primo ad ima de sub\ limibus corruit, quod nimirum condicionis sue dignitas\ in rationis celsitudinem quasi in aeris libertate suspenderat.\ Sed quia contra preceptum cibum contigit, per ventris concupiscen\ tiam ad terras venit, et quasi post volatum carnibus pascitur, quia illa libera contemplacionis inspiracula perdidit, et deor\ sum corporeis voluptatibus letatur” |

“Of the eagle

it

is rejected as unworthy of its kind and of such a father and, being unworthy

of being begotten, it is considered unworthy of being reared. The eagle

condemns it not in a harsh manner but with the honesty of a judge. He does

it, not as a father denying his own child, but as one rejecting another's.

seems to some, however, that the kindness of the common variety of the bird

excuses the unkindness of its regal counterpart. The ordinary bird is called

fulica, coot; in Greek,

fene. Taking up the eaglet,

abandoned or unacknowledged, the coot adds it to its brood, making it one of

the family, with the same maternal devotion as it shows to its own chicks,

and feeds and nourishes the eaglet and its own brood with equal attention. (…)

There

is an another interpretation. 'Like the eagle that hasteth to the prey'. The

eagle flies suspended at a great height and by the swift beating of its wings

hangs poised in the air, but because of the longings of its stomach, it seeks

the earth, hurling itself suddenly down from the heights. |

a. Bartholomaeus Anglicus[276]

“Dat ij. ca. vanden aern

Ende wi willen aenheffen te seg-

ghen inden eersten vanden aern want hi

houdt die principaetscap onder alle die

vogelen als een coninc ende hi is mildtste

van allen voghelen als plinius seyt \ want

een roef die hi vaet die en et hi alleen niet

ten si dat hi groten hongher heeft mer

hi deylten alle den genen mede die hen

na volgen mer hi neemt eerst sijn beco-

minghe ende daer om volgen die ander vo

gelen den aerne gheern opten hope dit

hem die aern wat mede deylen sal | en-

de als hem die roef dien hi eerst gevan

gen heeft niet genoech en is dat hi noch

tans daer af niet sadt ghenoech en is so

tast hi voert totten ghenen die hen naest is

die welke hoepte dat hem die aern wat

ghelaten soude hebben ende pluct ende

schoert dien oec ende also totten anderen

ter tijt toe dat hi sadt is ende dit doet hi

recht of hi een heer waer ende dattet al

sijn eyghen waer dat bi hem is so tast hi

toe ende en raect nyemants | ende dat hen dan

ouerloept die bi hen sijn Item hi pleecht twe

steen te leggen in sinen nest diemen ethe

res hiet vanden welken die een een man-

niken is ende dat ander een wijfken / of al

dus die een is manlic ende die ander wijflic

ende dese stenen leyt hi daer inden nest op

dat sise beschermen sullen vanden ete der

serpenten ende vanden vanijnden crupen

den dyeren als plinius seyt Item die aern

is seer scarp van gesicht als ysidorus seyt

want als hi bouen der zee inder luchten

helt stil mit sinen vloeghelen so vliecht

hi alsoe dats gheen mench bescouden

en mach nochtans siet hi wel vander bouen

cleyne visschelkijns inden water ende coemt

van bouen ende grijptse ende als hijse ghe-

vanghen heeft soe vliecht hi opt oeuer

ende aeset dat hi geroeft heeft Ende het is

natuerliken een hete ende een droghe vo

ghel ende is ghierich opten roef ende star-

ke ende stonte bouen anderen vogelen \ en-

de sijn starckeyt leyt seer inden voeten ende

inden vloeghelen ende inden becke want

sijn vloegelen sijn seer zenich ende niet vley

schich ende daer om mach hi wel arbeyden

inden vliegen om dit hi heeft veel pen-

nen ende groot waer af dat hy lichteliken

vliecht. Item die aern siet scarpeliker dan

enich ander vogel want hi heeft dit gees

telike gesicht alte sonderlinge seer ghe

tempert ende hi siet int rat der sonnen als

si alre schoenste schijnt sonder verbraeu

wen of hi siet in die circumferencie des

raeds vander sonnen sonder wederslach der

oghen \ ende tscarp van sinen gesichten

worter niet af geplomt als ambrosius seyt

Item die selve seyt als aristotiles dat-

ter eenrehande ghedaenten van aernen

sijn die si almathor hieten sie seer scarp

gesicht hebben die welke haer ionghen te

ghen der sonnen setten ende latense daer

in sien ende ist also dat si niet en salgieren

inden sien so houdt hise voer hem ende ist

anders soe houdt hijse voer bastaerden

ende stoetze uten nest of dootse Item aristotiles

seyt dit die vogelen mitten crommen claeu-

wen behoeuen scarp ghesicht van node

want si sien van seer verre haer spise en-

de daer om heft hen die aern veel hoger

dan die ander vogelen ende daer om mestelt

hi oec in hoghen steenroetsen ende be-

schermt hem selven daer van allen die hem

deren mogen. Waer af gregorius seyt \ hi

sicht inden alre hoechsten seker / mer hi

moet sijn voetsel beneden halen ende soec-

ken ende al ist dat hi onmaten hoge inder

luchten is nochtans als hi een vulic siet

so is hi haest neder | het wort den aern seer

zuer dat hi broedt ende kuken voedt. als aristotiles seyt li. vi. ende hi en seyt ten hoech

sten bouen drie eyeren niet mer dat derde

werpt hi vanden nest ende hi wordt also

crancker dan als hi broedt dat hi ander

ionge voghelen niet biten en mach want

sijn clauwen werden hem te crom ende

sijn vederen werden wit ende so wortet hem

alte zuer dit hi sinen ionghen teten be-

werven moet want gevallet dat hi drie

iongen crijcht so stoot hi dat derde uten

nest om des wil dat hijs niet voeden en

mach mer die voghel kun diemand in a

rabics cobar hiet die neemt dese ionghe

die de aern uten nest gheworpen heeft

ende voetse lichamelick als die selve seyt

Item daer sijn diuerse ende menigerhan

de aernen ende si en broeden noch en voe-

den niet alleens want die witte starten heb

ben die arbeyden meest in horen broeden ende

die enen swarten hebben dien verdrietes

want desen stoten haer vluchs uten nest

als si vliegen mogen ende si latense ver-

hongheren op dat si te bat den ouders

volgen sullen inder luchten om haer aes

ende wanneer dat die ouden sien dat die ion

ghen traghen so biten sise ende slaense ende

nemen hem haer spise ende als si sien

dat si starck genoech sijn te vliegen so ia

gen sise mit allen en wech in een ander

lant van hem sonder een geslacht als a-

ristotiles seyt datmen achat hiet die welke

menich tijt denct op sijn ionghen so vliecht

die oude mede ende gheeft hen teten ende

waer daer enich ander vogel die den ion-

gen misdoen woude daer soude die ou

de voer vallen ende bescuddense Alle de-

se punten roert aristotiles li. vi. Item van

den aern wort gheseyt als gregorius roert

ouer iob. Dat wanneer die ionghesken

eerst geboren werden ende dat si geen gro-

ue spise in nemen en mogen so zuken die

oude dat bloet uten aze ende dat bloet ge

nen si den iongen ter tijt toe dat si groue

spise nemen moghen. Item noch seyt au

gustinus ende plinius \ dat die aern in sinen ou

derdom donckerheyt in sinen ogen crij

ghet ende swaricheyt in sinen vloeghelen te

gen welc ongemack hi geleert wort van

der naturen dit hi een coude fonteyn soe-

ket ende als hi die wel weet so climt hi op

also hoge inder luchten als hi climmen ende

vliegen mach dat hi te mael heet wert

ende als dan die sweetgaten open sijn ende

die vederen ontbonden ende geslappet ende

dan al neder dalende valt hi in die fon-

teyn ende daer werden hem sijn plumen ende

vederen verwandelt | ende die duysterheyt

inden ogen wert ghesimert ende daer crij-

ghet hi sijn crachten al weder Item ouer

den souter seyt oec die selue dit wanneer

hi oudt wert so wert sijn beck also hart

ende alsoe crom dat hi cume spisen nemen

mach ende \ daer tegen heeft hi enen reat

geuonden. Want hi soect een steenroets

daer hy den nebbe hardeliken teghen

slaet en wrijften ende also doet hi den last

des becx af ende als hi dan weder spise

neemt so crijcht hi sijn crachten weder ende

wort weder ionck endestarck als plinius

seyt. Item die aern als hi staet op een steen

roets of op enen boem ende stuert die scar-

picheyt der oghen totter claerheyt der

sonen of naden roef soe siet hi alom ghens

ende harwaert of hi en laet niet af sijn na-

gel aen te sien Item die gal vanden aern

is seer goet ter medecinen want wanneer

datmense doet in collirien so scarpt si tge

sicht \ collirium dat is een medecijn die

men waect totten oghen ende alsmen die

gal mede in dier medecinen doet soe is

dat collirium of die medecijnen te beter Dit

seyt dyalcorides ende constan. Item die aern

heeft sommige goede proprieteyten het

is een vogel die den anderen voghelen

bouen gaet inder broecheyt ende inder het

ten \ ende daer om is hi stoute ende schier

gram want die gramscappen en is niet

dan inden lichamen van groter droech

ten als aristotiles seyt li. xvi. Ende die aern is

viant der onnoselre vogelen. Hi grijptse

mit sinen claeuwen ende smijdt hair hoeft

mit sinen beck ende hi heeft een stemme

daer die ander voghelen af veruaet sijn

als sise horen Item alle ander voghelen

sijn va hem veruaert sijn si rouers of en

sijn si gheen. waer af dit plinius seyt dat

die valck ende dye ander vogelen opter aer

den vaet ende si en ontsien die aern niet mit

alien die inden water die vogelen vangt

wtgenomen die vogelen die inden wa-

ter haer nootdorst soeken moeten want die vogelen ontsienen wel mer anders

gheen Ende dese leste sye de vogelen int

water vangt is veel on edelre dan die an

der die inder lucht en proyet of inder aer-

den Ende die selve onedel ontsiet den ghier

alte seer waer af dat aristotiles seyt in li. xx.

Dat amathel dat is dese onedel aerne

blijft bijder zee ende bi groten staenden wa

teren daer wacht hi die vogelen die in-

den water haer voetsel nemen mer ist dit

hi den ghier siet so is hi vernaert ende

vliecht dan int water. Ende als dat die

ghier siet die welke scarp van ghesicht

is vliecht altoes omtrent al om ende om

verre daer af Ende ist dat dese onedel aer

ne uten water vliecht inder luchten of op

tlant so is die ghier daer ghereet ende

ggrijpt den aern \ ende waert dat dese one-

del aern lange inden water bleue so sou

de hi smoren of drencken ende daer om is

hi daer qualiken aen als die ghier sijns

verbeydt want hi moet drencken. Of hi moet vanden ghier gedoot werden | ende de

se aerne heeft enen helen voet als een

gans daer hi mede zwemt. ende hi heeft

enen gesplitten voet als enen aern dair

hi die voghelen mede grijpt Item die

penne van enen aern heeft een verbor-

gen vretende craft als plinius seyt Want

hi seyt aerns vederen verderuen die ander

vederen mit allen ghelikerwijs dat een

coerde van enen wolue gemaect van si

nen darmen ende die coerde of snaer ghe

set op een ghytaern of op vedel bi sna-

ren die gemaect waren van scaeps dar-

men verderftse alle gader als die selve

seyt. Item die aern en begeert mit geen

geselscap te wesen mer hi wil alleen we-

sen als aristotiles seyt li. i. want dese crom

becte vogelen en begheren nyemants

geselscap Item die aern heeft claeuwen

voer sijn wapen ende daer om als hi coemt

te staen op een steenroets so trect hi sijn

claeuwen in ende sluytse bi na inden vleysch

op dat si niet plomp werden en sullen ende hy

is wreet tegen sijn iongen als hi siet dit si

haer geischt sluten tegen der sonnen want

so meynt hi datse sijn niet en sijn ende hy

pleechtse te slaen mitten becke ende te

schoren mitten claeuwen als si niet biten

en willen als

plinius seyt.”

c. Albertus Magnus

“|7| 1. AQUILA (Eagle) is so named from its “acumine” (sharpness). For, the eagle displays three modes of sharpness: an acuity of vision; a cutting rage; and razorlike claws and beak with which it hunts for prey. Every species of eagle is noted for its sharp sight, especially that noble bird known as “herodius” in Latin. The latter is called by this name as if it were the “heros” (hero) of all birds.

The eagle is a massive dark-colored bird whose dorsal and wing feathers change to ash-grey as it grows old. It has bright yellow feet, long powerful talons, and a large grey-black beak. Its wings are broad and flat, composed of straight feathers whose tips are slightly separated and curved upward. Soaring at great heights, it is able to gaze directly at the sun’s disk, so great is its power of vision; for this reason, the story goes that the eagle suspends its nestlings over the edge of the nest and ousts those which are unable to stare at the sun without shedding tears. According to another story, a bird called “fehit” in Greek and “fulica” in Latin, gathers up the rejected eaglets and rears them as its own. But this tale must be false, because the “fehit” is supposedly a species of dove which under no circumstances would give nurture to an eagle; and the “fulica,” also called the black diver, is a species of aquatic bird, smaller than a duck and just as unlikely to feed an eagle. In point of fact, neither of these species has a diet comparable to any of the eagles.

|8| Various authors assign different reasons for this ejection of eagle fledglings from the nest. Some claim the parent bird abandons the fledgling because it senses the species would be weakened by the survival of such offspring; the same writers concede the possibility of an occasional mating of a female eagle with a male of a species other than the golden eagle; but we deem this improbable. Other say an eagle of another species substitutes its eggs for the broken eggs of a golden eagle; in this case, after the eggs are hatched, the brooding parent is driven to prove the presence of an alien eaglet in its nest. However, the golden eagle is a bird of consummate ferocity and is believed to be gifted with some sort of prescience which allows it to detect the approach of an enemy to its nest, even at a distance. In any event, it would seem there is no species of bird so audacious it would dare to intrude upon the nest of a golden eagle. Moreover, the practice of substituting eggs into a strange nest is limited to the very lowest and inferior birds which are incapable of hatching their own eggs; birds of this type would never approach a golden eagle’s nest. Still other writers allege the golden eagle itself substitutes its eggs for those of another species, intermingling them with the eggs of an alien brooder; when the eggs have hatched, the golden eagle returns to the proxy’s nest out of affection for its own offspring. It distinguishes its own progeny from those of the proxy by forcing them to gaze at the sun; after separating the two, it nurtures its own young and ejects the others, which are then gathered up and fed by the female eagle which hatched them. I think this explanation is more credible, if indeed the eagle’s rejection of nestlings has been accurately observed and reported. Brooding over eggs is an onerous task requiring constant attention, and often leads to loss of weight in the female due to deprivation of her normal diet, a condition not well tolerated by the golden eagle whose far-reaching flights accustom it to an abundant food supply. In summary, it can be stated with fair accuracy the cause of the ejection is not prompted by the discovery of pseudo-eaglets nor by a prior insertion of eggs for another species. Just as the full power of nature is sometimes impaired in other animals, so also can this occur in offspring of the golden eagle; when the parent detects this weakness in the eaglet’s eyes, it rejects the nestling as useless.

|9| Some philosophers maintain the golden eagle produces two or three chicks in a brood; but, since it lays only two eggs at a time, two must hatch from one egg, and one from the other. I think this is false. A more likely explanation is that, though the eagle is a large bird, relatively little of its substance goes into the formation of semen; on this account it lays only one or two eggs, or perhaps a third if it is a young adult; only a single chick hatches from each egg, except as a freak of nature as sometimes occurs in other birds; but when more than two chicks are born, the parent usually rejects the extra offspring because of the difficulty in feeding a larger brood. This phenomenon of rejection has been observed frequently in many bird species. As I pointed out before, conversations with many experienced bird catchers have convinced me that the golden eagle seldom has more than one offspring within a span of several years, for the simple reason that the growing eaglet requires a great deal of food which must be sought far and wide by the older eagles. When two fledglings are found in a nest, this usually occurs in the northern regions near forests and the sea, where fish and birds may be plundered and great numbers of small wild animals are available as prey.(...)

|10| I have no personal knowledge about the truth of a claim which Jorach and Adelinus make for this eagle. They maintain when the young eagles have reached maternity and possess the knowledge and agility to hunt for themselves, the aging parent searches for a bubbling spring of clear, deep-flowing water. After it finds the spring, the older eagle soars straight up into the air above the water until it attains the third stratum of the atmosphere which we designated “aestus” in our book On Meteorology. When the bird absorbs the heat of this atmospheric level and seems almost ready to be burned to a crisp, it retracts its wings and plummets headlong to the earth, plunging into the cold waters of the spring. The coldness causes its internal body heat to be retracted from the surface of its body and to be concentrated within its very marrows. Then, bursting forth from the spring, the eagle flies straightaway to its nearby nest, where the younger eagles blanket it with their wings and induce it to sweat. By shedding its old feathers the eagle loses the appearance of aging and beings to grow a crop of new down-feathers. Until the new feathers have sprouted, the elder eagle is sustained by plunder provided by the young eagles. I am at a loss to explain this phenomenon, except to say there are untold marvels in nature. What I have observed in the behavior of two golden eagles in our country does not correspond with the tales of these authors; but then, the eagles I have studied were domesticated and trained to the role of other birds of the hunt[277].”

d. Brunetto Latini

“CXXXXV DE L’AIGLE

AIGLE est li mieus veans oiseaus du monde; et vole si en haut k’ele n’apert pas a la veue des homes, mais il voit si clerement, que neis les petites bestes connoist ele en terre et les poissons es euues, et les prent en son descendre. 2. Et sa nature est de garder contre le soleil si fermement que ses oils ne remuent goute; et pour çou prent l’aigle ses fiz esgarde justement sans croller est tenus et norris si come dignes, et celui ki les iex remue est refusés et getés du nit comme bastars. 3. Et ce n’est pas cruauté de nature, mais pour jugement de droiture, car li aigle ne la chace pas pour son fiz, mais comme autrui estrange. Et sachiés que .i. vil oisel, ki est apelés fulica, acomplist la fierté du roial oisel; car ele reçoit celui entre ses fiz et le norrist comme ses fiz.

4. Et sachiés que aigle vit longhement por ce k’ele se renovele et depose sa viellece. Et dient li plusour k’ele vole en si haut leu vers la chalour du soleil que ses pennes ardent; et oste toute l’oscurité de ses iols, et lors se laisse cheir en aucune fontaine ou ele se baigne .iii. fois, et maintenant est joene come a son comencement. 5. Li autre dient ke le bek de l’aigle croist et plie en son grant aage, en tel maniere k’ele ne puet mais penre de ces bons oiseaus ki la maintenoient en vie et en jounece; lors * le fiert maintenant et aguise tant as roides pieres que le sorplus s’en oste, et son bek vient plus gens et || plus esmolus que devant, si k’ele menguë et renovele et prent ce ke li plest[278].”

e. Jacob van Maerlant[279]

“Aquila es / die haren

sente augustijn / seit te waren

dat hi coninc / es teuoren

bouen alle vogle utevercoren

dies uintmene ghecront ghescreuen

an proie leit al sijn leuen

so scarp siet hi dat hi ghedoghen

mach metter sie uan sinen oghen

dat int sonnescijn gheuesten mach

des sietmen up meneghen dach

dat hi gherne omme dit

metten oghen in de sonne sit

de haren plecht seit augustijn

alse sine jonc .i. deel groot sijn

dat hise metten clawen up heft

ende wie so dan die sonne beseft

die dan ebben so starke oghen

dat si die sonne conen ghedoghen

naturliker te scouwene ghinder

die houti ouer sine edele kinder

ende die hem van der sonnen veruard

houti ouer eenen bastard

ambrosius segt dat sulc spreect

dat hi sinen bastard uersteect

om dat hem uernoit ghinder

te uoedene so uele kinder

ende dat nes niet altoes sine sede

aer het doet sine ghierechede

ende om dat hi niet wille onturien

de edeleit uan sire partien

maer ambrosius segt ouer waer

dat .i. uoghel es ende hetet fulsica

nempt met hem die jonc uerdreuen

ende uoet den sinen beneuen

adelinus die meester sprect

alse die haren van houden breect

soeket hi ene fonteine cout

ende uliechter up met ghewout

bouen allen swerken segt hi

dar der sonnen vier comt bj

ende hem die donkereit van den ogen

der sonnen hitte doet uerdroghen //

dan ualt hi neder met ghewout

jn die diepe fonteine cout

driewaruen ter seluer vard

dan vlieghet hi te sinen neste ward

te sinen ionghen die sijn so houd

dat si te proien ebben ghewoud

versieket es hi inder ghebare

als of hi in enen rede ware

hi wert ontplumet dan moeten voeden

sine jonc ende broeden

ontier ende hi uerionghet ghinder

vp dit so merct gi quade kinder

[wat u stomme beesten leeren

die vader ende moeder gheneeren]

(…)

alle edele uogle te waren

ontsien ghemeenlike den aren

ende des daghes dat sine sien

wilsi qualike der proien plien

van dien gherualke seit die glose

doet den haren dicke nose

ende hine uaet merket die gherualke

bedieden wel die dorpar scalke

[die hem niet ne wille keren

onderdaen te sine haren heren

ende haer heerscap quetsen ende jaghen

des salse god der omme plaghen]

(…)”

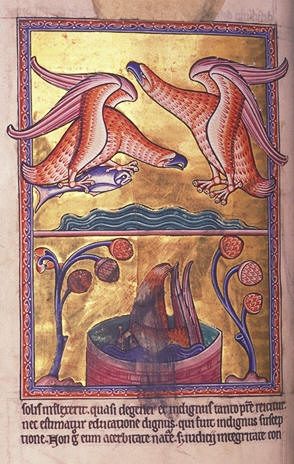

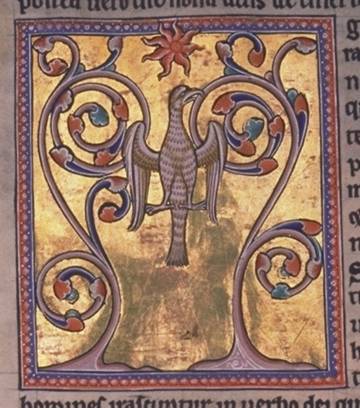

2. Illustraties

The Aberdeen Bestiary, [http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/comment/29vbird.hti], Ms. 24, folio 29v°.

JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, KA 16, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1350. [http://racer.kb.nl/pregvn/MIMI/MIMI_KA16/MIMI_KA16_074R_MIN.JPG], folio 74r °.

JACOB VAN MAERLANT. Der naturen bloeme. Manuscript KB, 76 E 4, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nederland, 1450. [http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/thumbsa300/76E4_037R_MINM.JPG], folio 37r °.

The Aberdeen Bestiary, [http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/comment/61v.hti], Ms. 24, folio 61v°.

Bijlage 4: De feniks

1. De bronnen

a. Physiologus

“IX. On the Phoenix

The Savior said in the Gospel, “I have the power to lay down my life, and I have the power to take it again” [John 10:18]. And the Jews were angered by his words. There is a species of bird in the land of India which is called the phoenix, which enters the wood of Lebanon after five hundred years and bathes his two wings in the fragrance. He then signals to the priest of Heliopolis (that is, the city named Heliopolis) during the new month, that is, Adar, which in Greek is called Farmuti or Phamenoth. When the priest has been signaled, he goes in to the altar and heaps it with brushwood. Then the bird enters Heliopolis laden with fragrance and mounts the altar, where he ignites the fire and burns himself up. The next day then the priest examines the altar and finds a worm in the ashes. On the second day, however, he finds a tiny birdling. On the third day he finds a huge eagle which taking flight greets the priest and goes off to his former abode.

If this species of bird has the power to kill himself in such a manner as to raise himself up, how foolish are those men who grow angry at the words of the Savior, “I have the power to lay down my life, and I have the power to take it again” [John 10:18]. The phoenix represents the person of the Savior since, descending from the heavens, he left his two wings full of good odors (that is, his best words) so that we, holding forth the labors of our hand, might return the pleasant spiritual odor to him in good works. Physiologus, therefore, speaks well of the phoenix[280].”

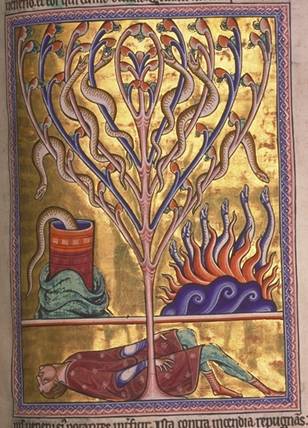

b. Aberdeens bestiarium

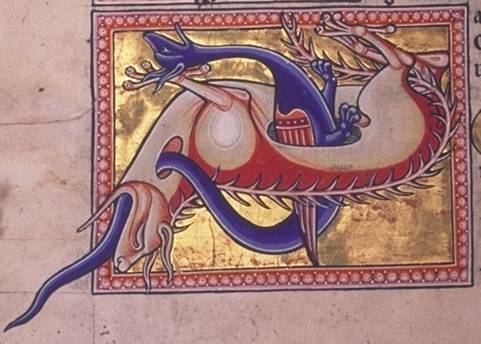

|

“[De fenice] \ Fenix Arabie avis dicta quod colorem feniceum\ habeat, vel quod sit in toto orbe singularis et\ unica.

Hec quingentos ultra annos vivens, dum\ se viderit senuisse, collectis aromatum virgultis, ro\ gum sibi instruit, et conversa ad radium solis alarum\ plausu voluntarium sibi incendium nutrit, seque urit.\ postea vero die nona avis de cineribus suis sur\ git.

Huius figu\ ram gerit dominus\ noster Jesus Christus qui dicit: Po\ testatem habeo\ ponendi ani\ mam meam et iterum su\ mendi eam.\ Si ergo fenix mor\ tificandi atque\ vivificandi se\ habet potesta\ tem, cur stulti\ homines irascuntur in verbo dei qui verus dei fi\ lius est qui dicit: Potestam habeo ponendi animam\ meam et iterum sumendi eam.

Descendit namque sal\ vator noster de celo ala[s] suas suavitatis odoribus novi et\ veteris testamenti replevit, et in ara crucis seip\ sum deo patri pro nobis optulit, et tercia die resur\ rexit.\

Fenix etiam significare potest resurrectionem\ iustorum, qui aromatibus virtutum collectis\ restaurationem prioris vigoris, post mortem sibi\ preparant.” … Fenix quoque\ avis in locis Arabie perhibetur degere, atque eam\ usque ad annos quingentos longeva etate procede\ re. Que cum sibi finem vite esse adverterit, facit\ sibi [de] thecam de thure et mirra et ceteris odo\ ribus in quam impleto vite sue tempore intrat\ et moritur. De cuius humore carnis exurgit ver\ mis paulatimque adolescit, ac processu statuti tem\ poris, induit alarum remigia, atque in superioris a\ vis speciem formamque reparatur.

Doceat nos igitur\ hec avis vel exemplo sui resurrectionem credere\ que et sine exemplo et sine rationis perceptione ip\ sa sibi insignia resurrectionis instaurat, et utique\ aves propter hominem sunt non homo propter avem.\ …

Sic igitur fenix incenditur, sed ex eius\ cinere fenix iterum nascitur vel procreatur. Cum ergo fenix mori\ tur, et ex eius cinere fenix iterum nascitur. Hoc exemplo agitur\ ut future resurrectionis veritas a singulis fieri credatur. Non est\ maius miraculum fides future resurrectionis, quam ex cinere\ facta resurrectio fenicis.

Ecce volucrum natura simplicibus\ resurrectionis augmentum [PL, argumentum] prestat, et quod scriptura\ predicat, opus nature confirmat. \” |

“[Of the phoenix]

...

The

phoenix also is said to live in places in Arabia and to reach the great age

of five hundred years. When it observes that the end of its life is at hand,

it makes a container for itself out of frankincense and myrrh and other

aromatic substances; when its time is come, it enters the covering and dies.

From the fluid of its flesh a worm arises and gradually grows to maturity;

when the appropriate time has come, it acquires wings to fly, and regains its

Previous appearance and form. …

In

this way, therefore, the phoenix is consumed by fire but from its ashes is

born or brought forth again. When it dies, it is also born again from its

ashes. The point of this example is that everyone should believe in the truth

of the resurrection to come. Faith in the resurrection to come is no more of

a miracle than the resurrection of the phoenix from its ashes. |

c. Bartholomaeus Anglicus[282]

“Dat xv. ca. vanden vogel fenix

fenix is een enich vogel opter we

relt waer af dit die leke luden hen verwonde

ren ende daer om heet hi in arabien daer hy

geboren wort singularis als ysidorus seyt van

desen vogel seyt die philosoeph \ dat fe

nix een vogel is leuende sonder gaye ccc.

ende vyftich iaer ende als die iaren om ghe

comen sijn ende dat hi gebreck gevoelt so

maecht hi enen nest van droghen wel ru

kende houte die welke ontsteken wer-

den als die sonne heet schijnt ende die zo-

den wint een luttel wayet ende als si ont-

steken sijn so gaet hi al willens vlieghen

in dat vierken ende wort daer tot puluer ende

tot asschen wt welker asschen binnen drien

dagen een wormken wast twelc alleyncs

ken vederen crijcht ende werdt een vogel

Dat selue seyt ambrosius in exameron

ende het is een alte schenen voghel ende is den paeuwe gelijc inden vederen ende hy

mint die eenlicheyt ende leeft van coerne

ende van suueren vruchten vanden welcken

alanus seyt Dat doe onyas die ouerste

bisscop in dyopolis der stat van egipten

enen tempel tot iherusalem is opten paesch

dach hadde hi doe een vierken gemaect

van wel rukende houtkens die seer licht

waren opten outaer om sacrifici te doen

ende ontstact openbaerliken daert alle die

luden saghen doe | quam die voghel fe

nix neder vlogen int vierken die welke

vluchs tot asschen wert. ende dye asschen

wert nauwe te rade gehouwen bi rade

des bisschops. Ende daer quam binnen drien

dagen een wormken af ende wort ten les

ten weder een vogel alst eerst was en-

de vloech en wech”

d. Albertus Magnus

“42. FENIX (Phoenix), according to some authors who devoted more attention to mystical themes than to the natural sciences, is supposed to be an Arabian bird found in parts of the East. These authors claim the bird is unisexual, lacking a male spouse and having no commingling of the sexes. They further allege that the phoenix, after coming into the world, lives a solitary life spanning three hundred and forty years.

The story goes, it is about as large as an eagle, has a crest on its head like a peacock and additional tufts on its jowls, and around its neck has a purple band with a golden sheen. Its tail is long and mauve-colored, marked with a geometric design resembling rosettes, in much the same way a peacock’s tail is marked with circles that look like eyes. In any event, this graphic pattern is supposedly of remarkable beauty. When the bird feels increasingly burdened by the rigors of old age, it selects a tall tree hidden in a copse above a lipid spring and builds a nest of twigs from frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon and other precious aromatic plants. Then it sinks into the nest, exposing itself to the burning rays of sun. The resplendence of its feathers magnifies the effects of the solar rays until both bird and nest burst into flame and burn to a crisp, leaving only a heap of ashes. On the next day, they claim, a sort of worm emerges from the ashes and within three days sprouts wings; in a few more days the winged grub is transformed into the likeness of the original bird and flies away.

These authors report an event which ostensibly occurred one time in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis where a native priest was the witness. A phoenix gathered branches from aromatic spice trees, built a structure from these sacrificial woods, set itself afire and, by the mode of reincarnation mentioned above, reappeared first as a worm, then turned into a bird and flew away. But as Plato says: “We ought not disparage those things reported to have been written in the books of the sacred temples[283].”

e. Brunetto Latini

“CLXII DOU FENIX